In 1984, volunteers Jay Schwartz, George Brooks, and John Hermann went into the Penn Museum’s storage collections. What they found amazed them.

As they would later write in Expedition magazine, “It is hoped that eventually some of this fascinating material ‘discovered’ in storage can be added to the present exhibit of monumental architecture from Merenptah’s palace already on display in the lower Egyptian gallery.”

It’s what Egyptian Section curator Joe Wegner would call “excavating in storage,” a phrase humorously applied to the idea that archaeologists have as much to discover in museum collections as they do by conducting new excavations in the field. Forty years after Schwartz, Brooks, and Hermann made their breathless realizations—and more than a century after the original excavation at Memphis—the towering potential of these discoveries is coming to fruition.

Between the Museum and two undisclosed conservation and storage annexes in New Jersey, the monuments of Merenptah’s palace and thousands of other Egyptian and Nubian artifacts are undergoing the latest treatments in preparation for their return to the renovated galleries starting in 2026. Head Conservator Molly Gleeson has been rolling up her sleeves: “This conservation work is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to study these ancient objects more closely than ever before. We are looking back on past practices, reflecting on how our field has evolved, and applying new technologies to prepare these pieces for display.” From beginning to end, the artifacts’ journey continues to be one of unprecedented engineering and ingenuity.

The gallery renovations will completely change the way visitors experience these artifacts. I can’t overstate the role that philanthropy has and will play in realizing this vision.”Christopher Woods, Penn Museum Williams Director

Starting with a Sphinx

To create space for the planned Egyptian gallery on the main level, an important early step of the renovation was moving the Museum’s beloved sphinx of Ramses II.

Dated to around 1200 BCE, the Penn Museum sphinx is the largest ancient sphinx in the Western Hemisphere and the fourth largest outside of Egypt. In October 1913, the sphinx traveled more than 6,000 miles by ship to arrive in South Philadelphia before continuing to Port Richmond, where it was transferred by crane to a railway car, then finally conveyed by a horse-drawn cart to the Museum. There, it was lifted over a wall and into the Museum courtyard by more than 50 men using a wooden derrick, beams, and a hoist. Years later, in 1926, the sphinx was placed atop a base of wooden railroad ties, and the Egyptian gallery’s walls were built around it.

In June 2019, a gantry and two hydraulic jacks delicately lifted the 13-ton, red-granite sphinx, which was then floated on a half-inch pillow of air created by four square “air dollies” fueled by high-powered air compressors. Similar to a disc on an air hockey table, the sphinx was pushed by a team of four along a 300-foot course to its new destination in the Museum’s entrance hall.

After the Egyptian galleries closed for renovations, the challenging process of moving thousands of pounds of monumental objects began.

Feats of Engineering

The Columns of Merenptah’s Palace

Accession numbers: E13576.1–6, E13577.1-5

The 3,200-year-old columns of Merenptah’s palace were originally to stand at full height in the upper level galleries, according to the 1920s schematics. But while the ceiling was designed to accommodate the full-height columns, previous engineers miscalculated the floor load capacity.

Now, a vision of towering columns, lintels, and gateways is being realized.

Stacking the columns to full height requires a massive, custom-made compression fixture, which can center, level, raise, and lower each piece of cylindrical limestone by clamping it between dozens of rubber-tipped feet. And the approach to completely stacking each column will be fine-tuned in the annex through a series of practice sessions and the fabrication of leveling interfaces, in preparation for the final display in the upper level galleries. It will be just one of many simulations before the actual move.

Assembled, the columns will measure about 30 feet tall and weigh about 15 tons apiece—roughly the weight of a cruise ship anchor.

Material Benefits

The columns are joined at the annex by a monumental throne room lintel and several palace doorways, which will debut at full scale in the renovated upper level galleries. To prepare them for display, conservators are addressing the effects of early interventions and rigorously testing materials to join and mount fragmented pieces in a non-invasive way. Says Senior Project Conservator Julia Commander, “Among other things, we’ve been thinking about our interventions with future conservators in mind. For example, to aesthetically complete missing areas on the doorways, we’ve magnetized high-density polyethylene inserts so they can be easily popped on and off. This is probably our last opportunity to do such extensive work for decades.”

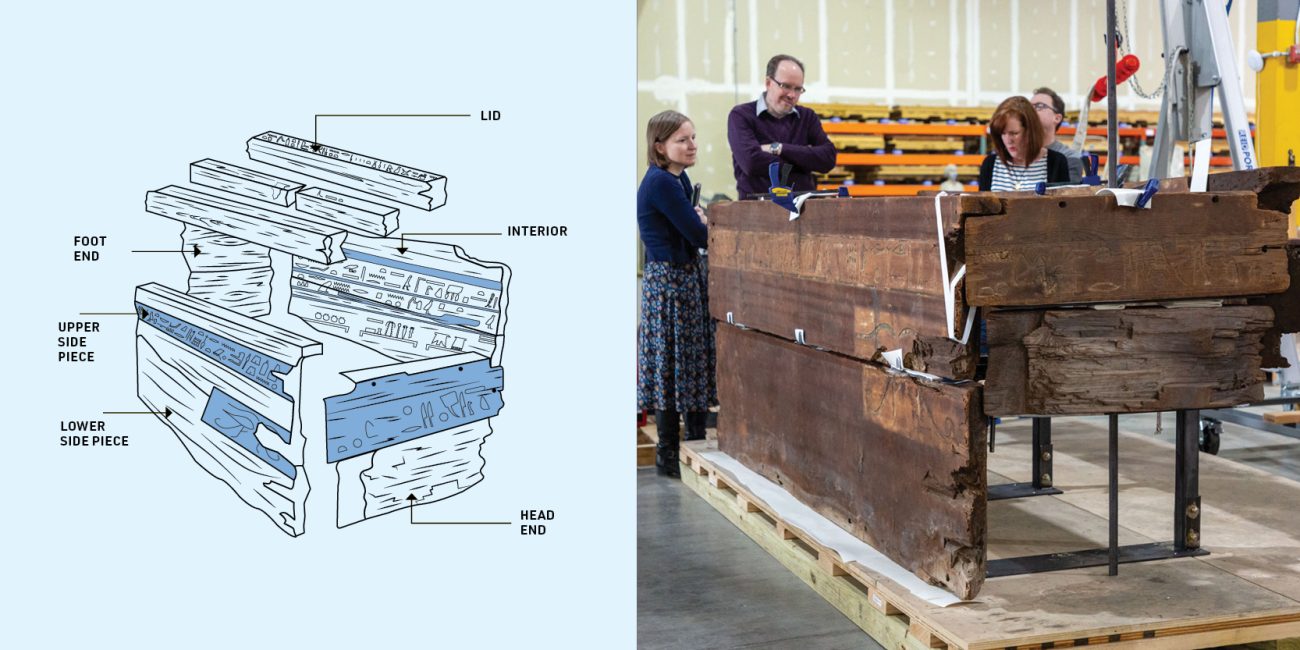

The Outer Coffin of Ahanakht

Accession number: E16218

This outer coffin is being carefully pieced together in one of the conservation annexes after being disassembled for over 100 years. At 4,000 years old, its cedar wood has naturally resisted insect damage and rot, and the coffin’s exterior remains vibrantly decorated with a carved and painted band of large hieroglyphs.

Ahanakht’s coffin presents a display challenge precisely because of its well-preserved state and extensive inscriptions. At about four feet high, the coffin would just allow a peek inside for some Museum visitors—but will it adequately display the coffin’s rich interior? The curatorial team of Jennifer Wegner, Josef Wegner, Kevin Cahail, and David Silverman is considering every angle. The interior is also inscribed with spells in hieratic, a cursive form of hieroglyphs, from a collection of funerary literature known as the Coffin Texts. How might the coffin’s lid be positioned in a way that allows its display without restricting the view? How could structural supports be positioned discreetly?

Philanthropy will be integral as the Egyptian and Nubian collections continue what will be a monumental journey—beyond the 40-mile return trip to the Museum, they will eventually be mounted and paired with specialized lighting, text panels, and interactive multimedia components. In the meantime? “It’s not just a matter of choosing a statue, putting it on a little box, and sticking it in a case,” jokes Jen Wegner. “It’s much more involved than that.”

Get Involved

Interested in more behind-the-scenes looks at the Museum’s progress? Want to get involved? The Museum is continuing to raise funds for object conservation and exhibition installation, critical to its goal of achieving operational storerooms and main level galleries by the end of 2026, and the upper level galleries by the end of 2028. Funding will support:

- Artifact conservation

- Exhibition development and installation

- Museum operations

- Educational programming